Tips

The Power of a Legal Document Generator AI in Modern Law Firms

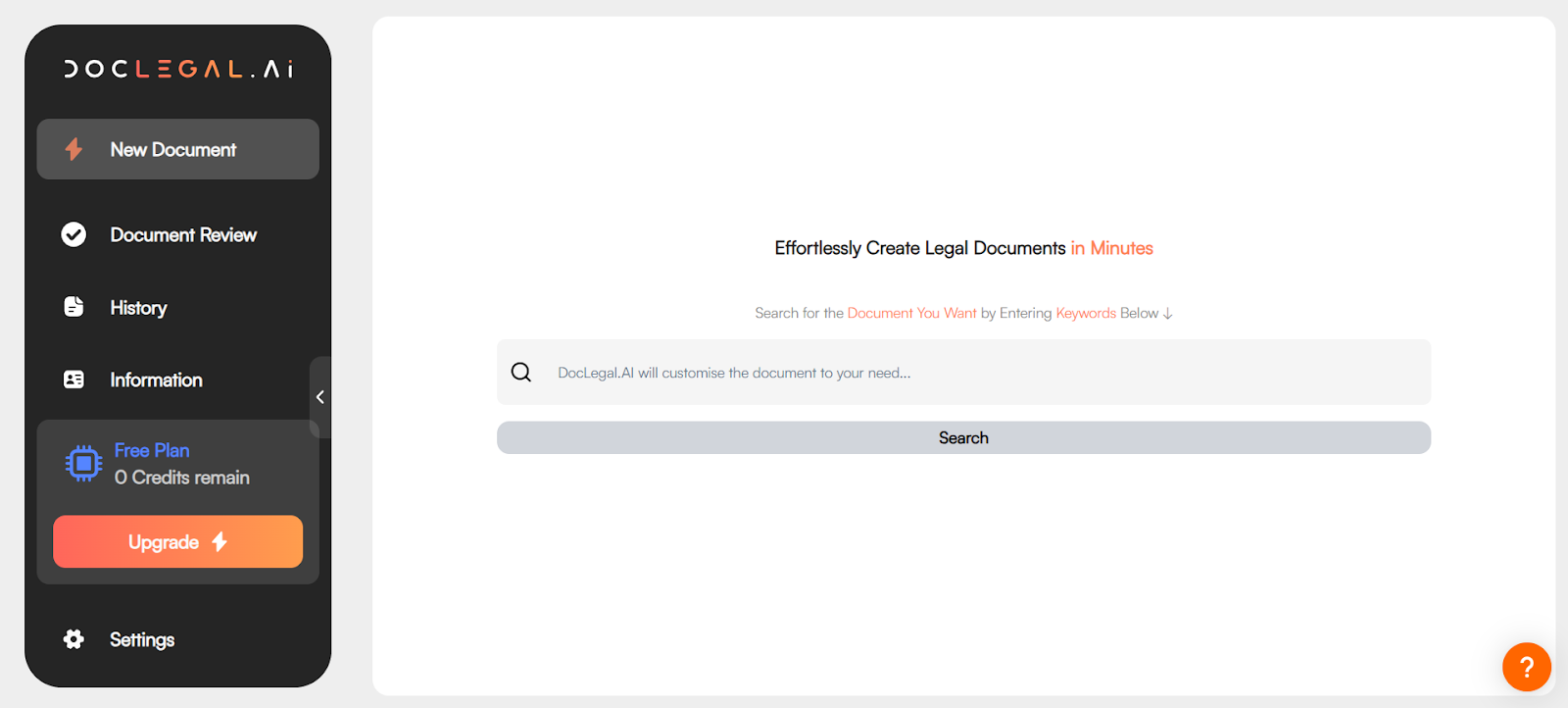

In the fast-evolving legal landscape, the integration of artificial intelligence has transformed how law firms operate. One of the most revolutionary innovations is the emergence of the Legal Document Generator AI, a tool that is reshaping the way legal professionals draft, review, and manage documents. With increasing pressure to deliver faster, more accurate legal services, modern law firms are turning to smart solutions like DocLegal.ai, our cutting-edge AI legal assistant, to stay ahead of the curve.This comprehensive guide explores the transformative power of AI in legal document automation, the benefits it brings to law firms, and how tools like DocLegal.ai are setting new standards in legal tech.

In the fast-evolving legal landscape, the integration of artificial intelligence has transformed how law firms operate. One of the most revolutionary innovations is the emergence of the Legal Document Generator AI, a tool that is reshaping the way legal professionals draft, review, and manage documents. With increasing pressure to deliver faster, more accurate legal services, modern law firms are turning to smart solutions like DocLegal.ai, our cutting-edge AI legal assistant, to stay ahead of the curve.

This comprehensive guide explores the transformative power of AI in legal document automation, the benefits it brings to law firms, and how tools like DocLegal.ai are setting new standards in legal tech.

Introduction to Legal Document Generator AI

Legal document automation is not a new concept, but the integration of artificial intelligence has elevated it to unprecedented levels. A Legal Document Generator AI uses machine learning and natural language processing to create, customize, and review legal documents with remarkable speed and precision.

Unlike traditional templates, AI-driven systems adapt to context, jurisdiction, and user intent, producing documents that are not only legally sound but also tailored to specific needs. With DocLegal.ai, legal professionals can now generate contracts, agreements, NDAs, wills, and more—within minutes.

🚀 Try DocLegal.ai now and experience the future of legal drafting: Start for Free

Why Traditional Legal Drafting Is No Longer Enough

The conventional method of drafting legal documents is time-consuming, prone to human error, and often inefficient. In an era where clients demand faster turnaround and greater transparency, law firms can no longer rely solely on manual processes.

Challenges of Traditional Drafting:

- Repetitive tasks reduce productivity

- High risk of inconsistencies and errors

- Time-intensive document review processes

- Limited scalability for growing firms

- Increased operational costs

Read More - The Problem: Contract Review Work Slows You Down

Modern firms need agile solutions. This is where AI-powered tools like DocLegal.ai step in to streamline operations and enhance accuracy.

Key Features of an AI-Powered Legal Assistant

An advanced AI legal assistant like DocLegal.ai brings a suite of intelligent features that transform how legal professionals handle documents.

Core Capabilities:

- 🧠 Contextual Drafting: Understands legal language and adapts to specific clauses

- 📄 Template Customization: Offers dynamic templates for various legal needs

- 🔍 Automated Review: Flags inconsistencies, missing clauses, and legal risks

- 🌐 Jurisdictional Adaptation: Adjusts content based on local laws and regulations

✅ Discover how DocLegal.ai can enhance your legal practice: Explore Features

Read more about AI Powered Legal Document Generator Explained: Faster, Smarter Contracts.

Benefits of Using DocLegal.ai in Your Law Firm

Implementing DocLegal.ai in your legal practice offers a wide array of advantages that go beyond just speed.

Strategic Advantages:

- ⏱️ Time Efficiency: Draft documents in minutes, not hours

- 💼 Professional Accuracy: Reduce errors and ensure legal compliance

- 📈 Scalability: Handle more clients without increasing overhead

- 💡 Smart Suggestions: Receive AI-driven recommendations for clauses and language

Still have doubts? Find out for yourself: “Is DocLegal.ai better than other AI tools? Google AI Overview Responds”

Real-World Applications in Legal Practice

AI document generators are not just theoretical tools—they are actively transforming legal workflows across various practice areas.

Use Cases:

- Corporate Law: Draft shareholder agreements, M&A documents, and board resolutions

- Real Estate: Generate lease agreements, purchase contracts, and disclosures

- Family Law: Create wills, divorce settlements, and custody agreements

- Employment Law: Automate employment contracts, NDAs, and HR policies

- Litigation: Prepare pleadings, motions, and discovery documents

📘 See how firms can use DocLegal.ai in real scenarios: Use Cases

Embrace the Future with DocLegal.ai

The legal profession is evolving, and those who adapt will thrive. With the power of AI-driven legal document generation, law firms can enhance efficiency, reduce errors, and deliver superior client service.

DocLegal.ai is more than a tool—it's your intelligent legal partner. Whether you're drafting a simple NDA or a complex merger agreement, DocLegal.ai empowers you to do it faster, smarter, and more securely.

🚀 Ready to revolutionize your legal workflow? Start Using DocLegal.ai Today

Contracts 101: 6 Essential Elements of a Valid Contract

Dive into the six vital elements of a valid contract in this exciting 2025 guide! Uncover the power of offer, acceptance, consideration, and beyond, with insights on privity and unilateral contracts. A thrilling case study reveals the offer vs. invitation to treat showdown in action!

6 Essential Elements of a Valid Contract

Contracts form the backbone of society by establishing trust and minimising risks between parties. A contract involves an exchange of promises or actions where one party offers value in return for something from the other. Contracts are not always monetary; they can involve specific performance of obligations or agreements to refrain from certain actions, such as non-compete clauses. A valid contract creates legally binding obligations, allowing a party to pursue a civil claim for a breach. This article explores:

(A) the six essential elements of a valid contract,

(B) privity of contract,

(C) the significance of unilateral contracts, and

(D) additional considerations in contract law, followed by a case study.

A. 6 Essential Elements of a Valid Contract

Many assume a contract is formed once an offer is made and accepted, but more is required for legal enforceability. Contracts can be formal or informal, written or oral, yet must include specific elements to be binding.

What are the 6 essential elements of a valid contract?

A contract is valid and legally binding if the following six elements are present:

- Offer

- Acceptance

- Consideration

- Intention to create legal relations

- Legality and capacity

- Certainty

1. Offer

An offer is a clear, definite proposal with specific terms from one party to another, forming the foundation of a contract. The offer and acceptance framework identifies a "meeting of the minds," where parties agree on terms.

What is the difference between an 'Offer' and an 'Invitation to Treat'?

An offer can be accepted to form a binding contract, while an invitation to treat is an indication of willingness to negotiate and is not binding.

For example, a store displaying products with prices is an invitation to treat, inviting negotiation rather than committing to terms.

An invitation to treat becomes an offer only when its terms are clear, definite, and leave no room for further negotiation.

Examples of an 'Offer' and an 'Invitation to Treat'

An invitation to tender is typically an invitation to treat unless it explicitly states that the most competitive bid will be accepted, making it an offer. Advertisements are generally invitations to treat, but specific promises with clear terms can constitute offers, as seen in unilateral contracts.

2. Acceptance

Acceptance is an unqualified agreement to an offer’s terms, expressed through words or conduct. A counteroffer, altering the original terms, does not constitute acceptance.

Acceptance must typically be communicated to the offeror, and silence is generally not acceptance, except in rare cases where prior dealings imply consent through conduct.

3. Intention to Create Legal Relations

Both parties must intend the agreement to be legally binding. Agreements labelled "subject to contract" or lacking clarity on essential terms may not be enforceable.

Domestic or social agreements are often presumed not to be legally binding, and agreements to agree in the future may be void due to a lack of intention.

4. Consideration

Consideration is essential for a contract’s enforceability, involving something of value given by the promisee (a benefit to the promisor or detriment to the promisee).

Consideration need not be of equal value, but must exist. If absent, the agreement must be formalised as a deed, which requires specific execution, such as being under seal.

5. Legality and Capacity

What renders a contract illegal?

A contract is illegal and unenforceable if it involves an unlawful purpose, such as fraud or illegal activities. A severability clause can ensure that if one provision is illegal, the rest of the contract remains valid.

Who has the capacity to contract?

The law presumes capacity to contract, but minors (typically under 18) and mentally disordered individuals may lack full capacity. Minors can contract for "necessaries" (essential goods or services), and failure to pay can lead to a breach claim. Contracts with mentally incapable individuals are generally void unless they grant power of attorney to another party.

6. Certainty

A contract requires reasonably certain essential terms, such as price or consideration, to be enforceable. If these terms are unclear, the contract may be void. Courts may fill gaps in commercial contracts using mechanisms like prior dealings or implied terms, provided there is intent to be legally bound.

B. Who Can Enforce The Terms Of A Contract?

Privity of contract is a principle stating that only parties to a contract can enforce its terms or be subject to its obligations. Third parties cannot sue or be sued, even if the contract benefits them. For example, if Party A promises Party B to give a gift to Party C, Party C cannot enforce the promise.

However, in some regions, third parties may have statutory rights to enforce contract terms if the contract expressly allows it or confers a benefit on them. Parties can opt out by including a clause excluding third-party rights.

C. Types of Contracts - Unilateral Vs. Bilateral Contracts

- Unilateral Contracts

Unilateral contracts involve a promise in exchange for performance, where only one party makes a commitment until the other performs the requested act. A typical example of a unilateral contract is a reward poster for finding a lost dog. The owner of the dog promises to pay, but only if another person is able to find his/her lost dog.

Key Features of Unilateral Contracts

- Offer Open to the Public: Unilateral offers can be made to the general public, not a specific individual.

- Acceptance by Performance: The offeree accepts by completing the requested act, not by promising to do so.

- Revocation Limitations: In some jurisdictions, once the performance begins, the offeror may not revoke the offer if the offeree is reasonably acting in reliance on it.

- Bilateral Contracts

Bilateral contracts are agreements where both parties exchange mutual promises, each committing to fulfil specific obligations. Unlike unilateral contracts, which are binding only upon performance, bilateral contracts create obligations for both parties from the moment the agreement is formed. These contracts are the most common type in business and personal transactions, as they involve a mutual exchange of commitments, such as in sales agreements, leases, or employment contracts.

Key Features of Bilateral Contracts

- Mutual Obligations: Both parties are bound by their promises to perform specific actions, creating reciprocal duties.

- Acceptance by Promise: The contract is formed when both parties exchange promises, not when an act is performed.

- Revocability Before Performance: Either party may revoke the offer before acceptance, but once promises are exchanged, the contract is binding unless mutually agreed otherwise or specific legal conditions allow termination.

Comparison of Unilateral and Bilateral Contracts

Aspect

Unilateral Contract

Bilateral Contract

Nature of Commitment

One party makes a promise; the other performs an act.

Both parties exchange mutual promises.

Acceptance

Through performance of the requested act.

Through a promise to perform.

Obligation

Only the offeror is bound until performance occurs.

Both parties are bound upon exchanging promises.

Common Examples

Reward offers, contests, or promotional deals.

Sales agreements, leases, employment contracts.

Revocation

Cannot be revoked once performance begins.

Revocable before acceptance; binding after.

Parties Involved

Can be open to the public or a specific person.

Typically involves specific parties.

D. Additional Considerations in Contract Law

1. Misrepresentation

A contract may be voidable if one party makes a false statement of fact that induces the other to enter the contract. Misrepresentation must be material and relied upon by the other party.

2. Estoppel

Promissory estoppel may prevent a party from retracting a promise if the other party has relied on it to their detriment, even if no formal contract exists.

3. Unjust Enrichment

If one party benefits at another’s expense without a valid contract, courts may require restitution to prevent unjust enrichment, though this is not a contract law remedy.

4. Breach and Remedies

A breach occurs when a party fails to perform contractual obligations. Remedies include damages, specific performance, or injunctions, depending on the breach’s nature.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- Can a contract without consideration be enforced?

No, a contract lacking consideration is unenforceable unless formalised as a deed, which requires specific execution. - What is valid acceptance of a contract?

Valid acceptance is unconditional, clearly communicated, and aligns with the offer’s terms, expressed through words or conduct. - How can ambiguity in a contract be avoided?

Use clear language, include essential terms, and reflect both parties’ intentions. A checklist of clauses can help. - Is a contract signed by an intoxicated person valid?

If intoxication impairs understanding, the contract may be voidable, requiring the intoxicated party to revoke it. - Can a minor enter a valid contract?

Minors can contract for necessaries. Other contracts may be voidable at their discretion. - What happens if a contract term is illegal?

An illegal term may void the contract unless a severability clause preserves other provisions. - Does silence constitute acceptance?

Generally, silence is not acceptance unless prior dealings or conduct imply consent. - Can third parties enforce a contract?

In some regions, third parties can enforce terms if the contract allows or benefits them, unless excluded. - What is the difference between a deed and a contract?

A deed is a formal document under seal, not requiring consideration, while a contract requires consideration and mutual agreement.

Case Illustration - Offer vs Invitation to Treat

Background

Imagine Company X, a renowned music event organiser, launches a vibrant campaign to promote an exclusive concert featuring a world-famous artist. Eye-catching posters are displayed across city billboards, proclaiming: “Ultimate Concert Experience! Limited VIP Passes at $600 each, including backstage access. Only 100 passes available—grab yours now!”. To emphasise its commitment, Company X posts on its social media that it has reserved $60,000 in a dedicated account to ensure pass availability.

Individual Y, a passionate music fan, sees the poster and rushes to Company X’s online ticketing platform to purchase two VIP passes. The website indicates that the passes are sold out due to overwhelming demand. Disheartened, Individual Y submits their contact information through a waitlist form, hoping for additional passes. Later that day, Company X sends Individual Y a direct message: “Great news! We’ve released two extra VIP passes for the concert at $600 each. Reply by 10 PM tonight to secure them.” Excited, Individual Y responds within an hour, stating, “I’m in! I’ll take both passes and pay via your website tomorrow morning.”

When Individual Y attempts to complete the payment the next day, Company X informs them that the passes were mistakenly offered and have already been sold to another buyer, claiming the message was only an invitation to treat.

Analysis

This scenario highlights the critical distinction between an invitation to treat and an offer, evaluated through the six essential elements of a contract:

- Offer: The billboard posters are an invitation to treat, designed to attract interest without guaranteeing availability to all. They invite potential buyers to make offers, which Company X can accept or reject. However, the direct message to Individual Y is a clear and definite offer, specifying two VIP passes at $600 each with a 10 PM deadline for acceptance. The $60,000 reserve announced on social media reinforces Company X’s intent to be bound, distinguishing the message from a mere invitation to treat.

- Acceptance: Individual Y’s response, “I’m in! I’ll take both passes and pay via your website tomorrow morning,” is an unambiguous acceptance of the offer’s terms, communicated within the specified deadline. The offer did not require immediate payment as a condition of acceptance, so Individual Y’s commitment to pay the next day is sufficient.

- Consideration: Consideration exists in Individual Y’s promise to pay $1,200 for the two VIP passes (a benefit to Company X) in exchange for the passes, including backstage access (a benefit to Individual Y). The agreement to pay upon collection satisfies the requirement for consideration.

- Intention to Create Legal Relations: The direct message’s formal tone and the public announcement of the $60,000 reserve demonstrate Company X’s intent to create a legally binding agreement, countering their claim that it was merely promotional.

- Legality and Capacity: The purpose of th contract—selling concert passes—is lawful, and Individual Y, as a competent adult, has the capacity to contract.

- Certainty: The offer’s terms are clear: two VIP passes at $600 each, with a specific deadline for acceptance. No essential terms are ambiguous, ensuring the contract’s enforceability.

In this case, Company X’s argument that the direct message was an invitation to treat is weak, as the message’s specific terms and deadline indicate a clear offer. Similarly, their claim that immediate payment was required for acceptance lacks merit, as the offer did not stipulate this condition. In a bilateral contract like this, acceptance is completed through clear communication of agreement, not performance (such as payment). Therefore, Individual Y’s timely response formed a binding contract, and Company X’s refusal to provide the passes after allocating them to another buyer constitutes a potential breach. Individual Y could seek remedies, such as damages for the cost of comparable passes or, if the passes are unique, specific performance to compel delivery.

This scenario illustrates the importance of distinguishing between broad promotional invitations and specific offers in commercial transactions. Businesses must craft communications carefully to avoid unintended contractual obligations, particularly in direct interactions with consumers.

Need Help Drafting Your Contract?

If you’re ready to create a contract that’s legally sound, clear, and customised to your unique needs, DocLegal.AI has you covered. Our AI-powered platform makes it simple to generate professional contracts and other legal documents, ensuring you stay protected and compliant without the hassle. Get started with DocLegal.AI today and take the stress out of crafting agreements for your business ventures!

.jpg)